Kenya has introduced a bold initiative to connect its surplus of trained teachers with global job opportunities. Under this program, teachers aiming to work abroad must undergo mandatory medical screenings, including tests for conditions like HIV, Hepatitis, tuberculosis, and yellow fever.

Kenya has introduced a bold initiative to connect its surplus of trained teachers with global job opportunities. Under this program, teachers aiming to work abroad must undergo mandatory medical screenings, including tests for conditions like HIV, Hepatitis, tuberculosis, and yellow fever.

This requirement aligns with the health standards of many potential host countries.

The government-led program, “Mwalimu Majuu,” seeks to remedy underemployment in Kenya’s education sector by deploying over 350,000 unemployed teachers to 17 countries, such as the U.S., Germany, South Africa, and the Middle East.

To streamline the process, the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) and Kenya’s State Department of Diaspora Affairs have partnered to reduce bureaucratic delays, including issuing passports in just three days.

Countries like the U.S., Ireland, and Germany are particularly interested in Kenyan teachers for English instruction, while nations like South Africa seek Kiswahili-fluent educators. There’s also growing demand in the Middle East and Japan for teachers in specialized subjects such as special needs education, Islamic studies, and science.

The program also enforces structured recruitment through government-to-government agreements, ensuring fair terms, job security, and proper living conditions for deployed teachers.

Who Qualifies?

The program has specific qualifications. Applicants must have:

- Recognized degrees, diplomas, or certifications.

- Registration with the Teachers Service Commission (TSC).

- Impeccable professional and personal conduct as mandated by Chapter Six of Kenya’s Constitution.

Additional requirements vary by host country, potentially including language proficiency or professional certifications.

Selected teachers will also undergo a specialized orientation program covering areas such as cultural sensitivity, security, salary negotiations, and foreign educational systems.

TSC will maintain a centralized database to ensure transparency and fairness during candidate selection. Standardized contracts are expected to cover salaries, working hours, benefits, and repatriation terms.

However, there’s a catch: teachers with permanent and pensionable status in Kenya must resign before signing international contracts. Critics worry this policy might deter long-term participation, as rejoining the Kenyan education sector would require fresh applications.

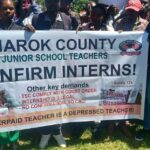

Kenya faces a paradox: an oversupply of trained teachers but insufficient full-time positions. For instance, a recent recruitment of 46,000 teaching roles received over 314,000 applications, highlighting severe competition for domestic jobs.

Meanwhile, public schools—especially junior secondary institutions—struggle with staff shortages.

Supporters argue that exporting teachers addresses unemployment and offers Kenyan educators improved salaries, international exposure, and professional development. Critics, however, fear it could exacerbate local staffing shortages, particularly under the Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC).

This initiative provides Kenyan teachers with opportunities for growth—exposure to diverse educational systems, updated teaching techniques, and financial security. These benefits could eventually elevate Kenya’s own education standards. Additionally, teacher remittances could boost Kenya’s economy.

The program is in line with President William Ruto’s vision of leveraging labor migration to tap into high-demand international markets—making it a cornerstone of Kenya’s job creation strategy.

Despite its potential, questions linger. Will “Mwalimu Majuu” alleviate unemployment or worsen the teacher shortage in Kenyan schools? Can the program balance local needs with the global benefits of teacher migration?

One thing is certain: this initiative could redefine teaching careers in Kenya and spark broader conversations about globalization in education.