He landed at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA) on Sunday morning before he joined faithful at Makadara Friends church in Eastlands Nairobi for a Thanksgiving service.

The 65-year-old announced his presidential bid and also challenged the country’s politicians to avoid insults and dirty politics ahead of 2022 polls. Ahead of his return to Kenya, he spoke to Sunday Nation about his presidential ambitions, the Building Bridges Initiative, Covid-19, and more.

Here are the interview excerpts:

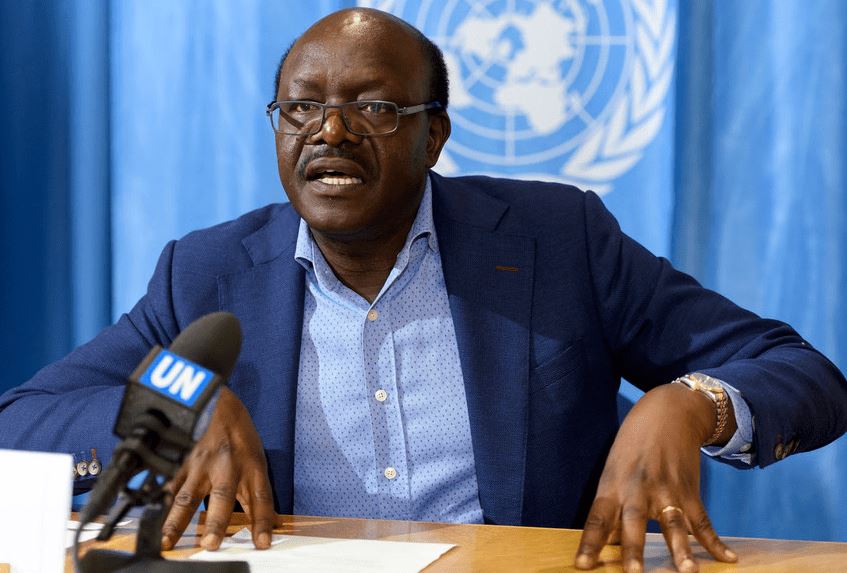

Why would you leave such a high-profile job (as Secretary-General of UNCTAD) to return to local politics?

I have been asked that question — and they do not always say ‘a high-profile job’, but ‘how do you leave such a high-paying job to come back home?’

For me, the journey of working for the United Nations over the past seven-and-a-half years has been that of learning, a journey of exposure and an opportunity to look at governance and empowerment issues and how societies conquer adversity. I thought that it would be a useful thing for me in my last active years to devote some time to see if I can be part of the team that can apply this trove of knowledge and exposure in dealing with national challenges of my home country.

I think at some point when you feel the patriotic call is there, you want to be the change that you desire. You have to be ready to take a risk and sacrifice personal convenience and the prestigious positions.

Just to be clear, are you running for President?

I have announced that I am starting the process of preliminary work with the intention of offering my candidature for President of Kenya. Of course, a number of preliminary things to do. The first one is by the culture of the Luhya community, from which I come, I must go and consult extensively among the key public leaders and cultural leaders of the community to seek their blessings. After that, I’ll address the nation on the direction of my candidature.

Second, I will need some time to get to know every part of the country. I’ve had the privilege to be in more places in Kenya than most people have, but I want to visit again — get to understand the people’s hopes and fears and try to see if my profound and acquired knowledge and experience can be relevant in the conversation around their challenges. So, there is a long way to go before I now say I’m in a position to bring this together as a force to be President of Kenya.

You say there is a long way to go but the reality is that it’s not too long to go before the 2022 elections So, do you have a political party or formation in place as we speak?

There is a political party in the making but I am not a lone-ranger. I am seeking to facilitate dialogue with different players. You know, I’ve had the privilege that I am the only aspirant for the presidency of Kenya who has never been in Tangatanga (a political grouping associated with Deputy President William Ruto) or Kieleweke (a political grouping associated with President Uhuru Kenyatta). I’ve never been in Nasa or Jubilee. So, I see myself as having the chance to bring comfort and assurance to people who have been across the divides. And so I would want to explore a journey of self-invention but also a journey of identifying people who are ready to work with me. I just hope that we can build a large enough coalition of nationalists interested in national solutions with purposeful politics that will address what I consider to be the key challenges at the moment.

But which party is this?

No, no, no. I don’t want to announce that right now.

I mean, if you ask Mt Kenya, will they tell you what party is going to be their main for the region in the next election? I think the identity of the party is not a front issue. Somehow people ask me what is your party and who is your running mate. I mean, these are questions that are not urgent right now. I think the main thing is that let me get into the journey of exploration.

There have been many false dawns in Kenya. What makes you think the Kenyan people will look at you differently?

You were saying there are many cases of false starts that is very true. I have no sense of entitlement neither do I come with any delusions that it is an easy task ahead. But I am driven by two very strong senses, one, that heroism has always come to those who are ready to take on the challenges that force them to get out of their comfort zones, whether materially or socially. But two, if some of us are not ready to take the risk that we may lose but we will try our best to win, then society will succumb to perpetual enactment of the politics that has held us back as a nation.

And I think I want to enter that national conversation, that there is more purpose to my candidature than “Project Kituyi”. We can shift the culture of our nation. If you reverse the political conversation and the narrative can be different from this polarising insult trading that we have seen for some time now.

The reality of our politics is that it largely revolves around ethnic kingpins and the alliances they build. What makes you think you will change this?

I have been a student of Kenyan politics most of my adult life. But I have for a long time been one of those leaders who don’t say ‘this is the way people behave, let’s behave along’. Instead, I say, ‘this is the right way for people to behave’. Can we find enough gravitas to shift the political culture in a certain direction? Remember what we did as Young Turks (in Ford) in the early 1990s— we did not play by the book.

To my mind, it’s a reality that at the end of the day in Kenyan politics, ethnicity matters. That’s why I’m dedicating the first period of my return home to go and consult and intensely engage the different segments of the Luhya community as a starting point. I’m painfully aware that if I cannot be relevant within the Luhya community, the rest of Kenya will not take me seriously regardless of how good the ideas I have for the nation. But having said that, I will not construct a narrative that I am a Luhya paramount chief. I need the credibility of my backyard to bring to a national discourse.

Well, to take you back to your answer, there is a long-running joke about Luhya unity and there is currently talk of Musalia Mudavadi of ANC working together with Moses Wetang’ula of Ford Kenya. How do you fit into this equation?

Many people might not remember that I sacrificed the chance of becoming Senator of Bungoma in 2013 to run the presidential campaign for Mudavadi. I was his campaign manager and I helped him to get four times as many votes in Bungoma as he got in Vihiga.

But there’s a second thing. I’m looking to offer national leadership in Kenya. I’ve not heard anybody talk about Gideon (Moi) and William Ruto discussing Kalenjin unity. And related to that, my sense of unity of people is not elite compromise — sitting down with Wetang’ula and saying let one of us be the president. Luhya unity should mean the potential voters of Luhyaland to become actual voters. How can you empower this community which has under-punched throughout its history in our national competitive politics, to pack its punches? Such mobilisation is the basis of a viable, sustainable, political unity of a community. If any of my colleagues performs a lot better than me on the score, I’ll be very comfortable to say ‘you seem to have the momentum and the rest of the country can accept you’. So to me the question of Luhya unity, which is discussed at funerals, is really an irrelevant narrative. The real basis of real unity is: do we have empathy and understanding of the challenges of this community.

Are there any ongoing talks between you and any key political players?

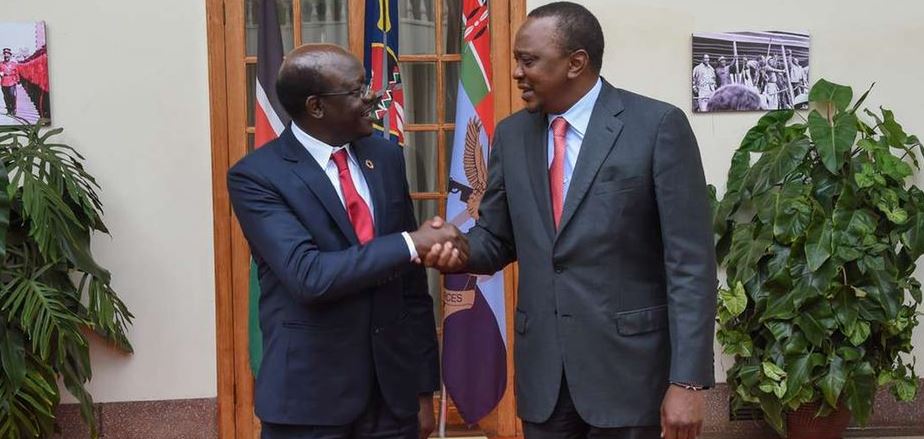

It’s important to know that that is the question I cannot candidly answer. I think I just want to specifically say that throughout my period as UNCTAD secretary-general, I have been a friend of the Government of Kenya, I’ve consulted, I have advised, I have shared my views on the way forward, at priority programmes with the president. Throughout the multi-party era, since the days when I was hiding Raila (Odinga) in my house and had to get him help to go to exile. Raila and I have been friends. I have consulted, I have disagreed on some things and agreed on other things. And in the past short period that I’ve been considering now offering my candidature, I have kept open doors to both of them and to a lot of other people – not in a way of saying, ‘please support my candidature’, but in saying ‘what is our national agenda; how can we stop the politics that polarises the society and hurts our economy at a particularly vulnerable time?’

I think maturity calls on me to be ready to talk to anybody and everybody in the country.

What would you say to those who think you’re not your own man, that you are somebody’s project?

They should show me which person in Kenyan politics is intellectually more mature than me. Which person in Kenya has a roadmap for national economic revival better than me? Which person in Kenyan politics has an idea about unlocking domestic and foreign investment? Which person in Kenyan politics has a passion for a clean struggle against corruption and has a track record of impeccable personal credentials on corruption? Show me that person then I will say I can consider becoming that person’s project.

What is your stand on the Building Bridges Initiative and the push to amend the 2010 constitution?

I appreciate the importance that the President and the former prime minister placed on BBI as part of national healing. I support national healing. I am aware that historical circumstances cannot repeat themselves about how you amend the constitution. There are some steps I would have preferred as a better way of a 10-year review of the 2010 constitution, but that is an irrelevant academic debate today. Where we are, my position, since there seems to be a consensus that they’re going to go with the consensus document on BBI. Let that process go on, but I don’t believe that a BBI on its own is a panacea of our national problems. So, while some have seen what they can grow for the national index out of BBI, I will try to offer ideas on complementary priority agenda, complimentary initiatives, that can also contribute to a more perfect republic.

Do you have a road map or timeline of what happens after your return today?

Yes, because as you know, I have in the past few months declined a lot of invitations to do media engagements precisely because it was an adult responsibility for me as a senior officer of the UN. So now is the first time in seven-and-a-half-years that responsibility and burden is removed from my shoulders. So, what I intend to do in the next week or so is to go through a deferred engagement with the media. Also, the process of working with my team for the consolidation of our secretariat and political party process. And then, as I mentioned to you, I go to Western Kenya, do some consultations intensively — including engaging, listening to and exchanging views with existing politicians of different levels. And then after that, I come back to the national platform to embark upon a tour of learning. I want to be part of writing a new conversation that is not elitist with one person who thinks he’s very clever and can tell Kenyans what they should do, but empowering people by saying our different opinions can be written on a shared canvas, which you carry together as our agenda for our new Kenya.

About the political formation you are working on, which you haven’t revealed so far: Is it closer to the axis revolving around President Kenyatta and Raila or Ruto?

If it is revolving around anybody, I think it will be more around President (Mwai) Kibaki… Who is no longer a political player…..

But he represents a certain moment in our history which recalibrated priorities in a certain way and it had an impact in the outcomes in the formation of political and economic governance. That is something that inspires me.

Does this mean you forming a sort of a third force?

No,no, no. I’m too old to go to do the adventure of third force. I want to offer Kenya the inclusive alternative. An alternative to the diversity of our needs, it shows empathy to those who are hurting because of difficult challenges in the economic times. It talks to those who are increasingly hopeless because of having gone a long time without having employment, collapsed business because of Covid-19, victims of red tape in starting up small business. And I also want to talk to the entrepreneur who at the end of the day enables the creation of jobs that will keep the promise to the hopeless and the vulnerable.

I don’t think you can easily box this into ‘are you with Raila and Uhuru, or with Ruto. I want Raila, Uhuru and Ruto to be with me.

As you leave your UNCTAD position, what would you say are the key achievements?

Well, basically I have finished the work of my second term because the only thing which is remaining for my task was to host UNCTAD 15 conference in Nairobi. This has now been postponed until October. But I have prepared a comprehensive secretary-general’s report to the world that I have shared with the board and I will share with the Kenyan media at the earliest opportunity. It says what is happening in the world. What are the challenges of the developing countries?

And what are the directions, the pathways for confronting and dealing with them and this is the normative leadership that I want to bring in the national conversation in Kenya. But most importantly, when I joined UNCTAD, many people in Kenya did not know the position of secretary-general had been advertised, and countries had presented candidates.

Recruitment had gone on and a shortlist of four names had been presented to the UN secretary-general (Ban Ki Moon). But a group of eminent development thinkers, including Kofi Annan, two former African presidents and International Development leaders wrote an open letter to Ban Ki Moon to say ‘we cannot interfere with your privilege to present a candidate… but this organisation is in a bad place…it needs a strong well-informed, but also engaging leader who will turn around…’

That is why Ban Ki-Moon cancelled the shortlist and invited me and two, three other people to go and do an interview as possible alternatives. From the day I joined the organisation, I said that UNCTAD was a Ferrari which had for a long time been locked up in a garage. And I said during my tenure, it is my mandate to polish this Ferrari, service it and put it on the road. If you listen to the unanimous voice from all the member states region, European Union, Eastern European countries Asian group, African group, the Caribbean, US, Canada, New Zealand and Japan, there was unanimity that I have done a brilliant job. I’m proud that today as the world discusses post-Covid recovery, UNCTAD is one of the players at the table of the UN grafting together with World Bank, IMF, about where we should go, and how we should go there. It is a singular achievement for me that I have unlocked the capacity of my staff in driving leadership in the world. I have been able to bring Africa in the centre of the discourse, you may get to know that UNCTAD opened an African office in Addis Ababa.

And it has become an important intellectual centre for bringing the concerns of Africa, and its matters to the world and fast-tracked the formation of the continental free trade area agreement, including training national teams on offering negotiations for trade, goods, intellectual property, singe airspace. Also importantly, my partnership with Jack Ma (Chinese billionaire and founder of Alibaba), where I have pulled a group of the young generation and given them skills to demand more from their individual country, states especially the possibilities in the digital economy.

These are some of the many achievements that I’m proud of but certainly if you ask the G20, the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) you ask the IMF, if you ask the rest of the UN, UNCTAD has made very, very, good progress beyond what I inherited in 2013.

Any regrets on what more you should have done to this UNCTAD Ferrari as you leave?

My only regret is that towards the end, the Covid-19 pandemic has so brutally destructed our momentum.

Are you optimistic about the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement?

I’ve said widely that, before I joined the UN, I was a consultant with African Union in developing the draft charter and the roadmap to the continental free trade area, including visiting 25 presidents to persuade them to sign up to the AfCFTA.

During my time at the UN, my organisation has been together with economic commission for Africa, perhaps most important partners of the AU commission in putting life in the text. What steps do we need to undertake on addressing fears? I believe in the concept of free trade area and seeing the way global value chains are now regionalising, from local going on the regional. Even if that (continental) initiative was not there before, African would still have needed to start an AfCFTA.

So, there is no doubting the importance of the AfCFTA, but that doesn’t mean that it’s an easy road to go. We still have fears among some economies that they don’t trust some of the African neighbours on administering rules of origin, for example.

How do I know that if I buy something written ‘made in Kenya’, it is genuinely made in Kenya and not made in Vietnam and rebranded as ‘made in Kenya’. So, these are issues that have to be dealt with. Political goodwill that is sometimes fluctuating, is a fickle commodity. But I think Africa needs a political leadership that is singularly focused on carrying the AfCFTA.

I applaud the initial role played by President (Paul) Kagame (of Rwanda), the President of Niger and the chair of the AU commission. But you need a few more champions of the continental free trade area at the highest political level to address the hurdles that are blocking the realisation of the dream. One of the issues of interest to me is if I am gifted with the privilege of being the President of Kenya, I would become the principal champion of AfCFTA.

We wouldn’t end this without talking about the pandemic, the vaccine and post-Covid-19 economic recovery for Africa in general and Kenya in particular…

I wish I could have started with the vaccine and then I can talk about the economy.

Alright, vaccine nationalism — how do developing countries navigate this to ensure equality while also getting the best out of Covax?

First of all, there is not going to be any equality and that is the saddest thing. The statement by the President of the European Commission (Ursula von der Leyen) about vaccine nationalism is the lowest point that anybody remembers from that important organisation. And I am glad, she did a quick retreat and realised it was a blunder. But in reality, in moments of uncertainty, many developing countries are on their own.

The (Covax) initiative can look like a charity of giving back to the developing countries but the reality is that all the vaccine developers of the world, apart from the Chinese vaccine Sinovac), is signing an agreement that all developing countries, including the whole of Africa, can only purchase their vaccine out of the Serum Institute of India and another institute that is manufacturing in South Korea. But these producers of the vaccine do not indemnify.

That indemnity over the possible negative consequences of the vaccine which are offered directly by the manufacturers. So we are more vulnerable to any negative consequences and cannot sue the producer, Further, the Serum Institute in India is selling to Africa the vaccine at higher prices than the vaccine is being sold to developed countries, almost 50 per cent higher.

But the slow roll out of the vaccine in Africa means that we will be stigmatised in the post-covid international travel—when a vaccination certificate is introduced, for example. And the foreign investor will not look at areas of continued pandemic stress.

This will obviously affect economic recovery…

That (vaccination) is one level. But there is another layer. In all societies, those that had built productive capacities are always much better suited for recovery after a crisis than the struggling. What this means is that those who have gone through structural transformations because of phenomenal productive capacity will be rebounding quickly in the economic down time and the impact is going to be much more in countries with lower productive capacity and means for structural transformations. The measures that we take are a challenge to us. What are the best practices, what are the levers that will make us recover better and with equity?

The vulnerable should also rise, not just stock exchanges, but Mama mboga, the youth, the unemployed, the lowly one without access to credit. This is the conversation about post-Covid economy, and my report to the UN which I have just submitted, lays out the pathway to recovery, to build productive capacity and touches on the new levers of the new service industry, unlocking the potential of the new digital economy. I wish these would be part of the conversation in our politics.