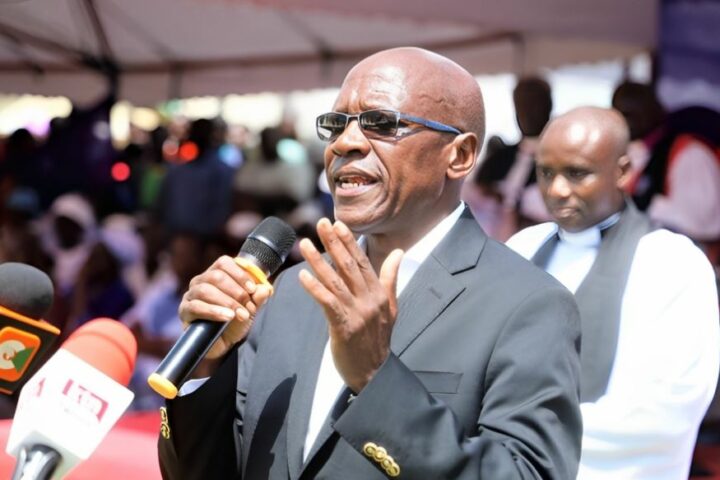

Harry Kimtai, the principal secretary, State Department for Livestock, spoke to ‘Seeds of Gold’ on challenges facing the meat sector and what opportunities investors can grab.

Harry Kimtai, the principal secretary, State Department for Livestock, spoke to ‘Seeds of Gold’ on challenges facing the meat sector and what opportunities investors can grab.

The price of beef has been on the rise, with a kilo going for an average of Sh500. What has occasioned the rise and how can the government change this situation if the industry is to grow?

The price is responding to the forces of demand and supply. The butchers are unable to get slaughter stock at a price they were used to before Covid-19 struck.

With Covid-19 protocols enforced, livestock movement within production regions was affected especially during lockdown leading to low supply of animals. The revamping of the Kenya Meat Commission (KMC), which was recently re-launched by the Head of State, President Uhuru Kenyatta, is another contributing factor to the rise in price of meat.

Previously, KMC was buying a kilo of live animals at Sh150. After the recent restructuring, the price shot up. The move has thus made supply to other slaughterhouses decline. Further, there has been drought in Kajiado and Northern Kenya, depressing supply.

How many beef animals (tonnes of meat) does the country need annually and are we producing enough?

Total meat production stands at 756,000 tonnes annually, 70 percent of it being beef, mutton (sheep) and chevon (goats) while white meat such as fish, chicken and pork occupy the rest. Red meat is the most consumed. Our per capita beef consumption is estimated to be about 12 kilos in every household per year. The rise in population, which stands at an average of 50 million, puts the demand at 600,000 metric tonnes yearly. The gap is augmented by regional livestock trade. There is enormous opportunity for investment in beef production.

Beef cattle farmers are grappling with a lack of market, which has seen them sell their animals at low prices to brokers. Can KMC come to the rescue of farmers?

Low supply of animals, poor marketing infrastructure and inadequate entrepreneurial skills are some of the challenges hurting beef farming. We are working on a model that will enhance group marketing and contract production for farmers to sell to established processors. These developments will become clearer when we finalise our livestock master plan and the beef strategy. Initially, when KMC was not performing well, farmers could sell their animals at low prices but now they have an option. The thing is that most farmers do not want to embrace the auctioning route.

The government was working on setting up feedlots in different parts of the country, even it went ahead to announce a tender for individuals to run the facilities. How close is your department in establishing the feedlots?

The government has purposed to establish feedlots in 13 arid and semi-arid land (Asal) counties namely Baringo, Kajiado, Narok, Isiolo, Marsabit, Wajir, Mandera, Tana River, Lamu, Garissa, Taita Taveta, Turkana, and West Pokot. The initiative is part of the Big 4 Agenda pillar of attaining 100 percent food and nutrition security.

The growing demand for meat is projected to reach 900,000 tonnes by 2022. We have initiated the establishment of feedlots, but we have not rolled out the programme yet. The government will provide land for holding grounds, and we have already received approval from the Cabinet on this. With the feedlot system of production, feeds will be grown, animals kept in a certain area and this will boost our production.

So far, we have identified 23 feeding lots across Asals, with Isiolo leading with 11,000 acres which will be subdivided for holding animals, growing of feeds and water harvesting.

The feedlots will also act as rescue centres for animals during severe drought. We are also planning to have value addition outlets, where processing of meat will take place and the final product taken to the market.

How has Covid-19 impacted on the livestock sector and what lessons have you learnt as a ministry in case a similar pandemic occurs in future?

With the health protocols, livestock movement within the regions became difficult, affecting the market. This pandemic has taught us that we should establish slaughter and processing outlets in production areas so that we transport processed products instead of live animals. We also need to invest more in ICT systems.

Kenya is losing its livestock export market to countries like Somalia and Sudan, why is this the case and how can this be reversed?

Our export market is not lost as such, we sell final products in Middle East countries and also Kuwait. But there is need to organise local farmers and producers for a competitive market. We do not have good infrastructure for the export market. As we work on it, controlling the outbreak of diseases has been a major challenge because of insufficient raw materials for making vaccines. Nonetheless, the Kenya Vaccines Production Institute has addressed the issue. If we sort out our vaccination programme, we will meet export market requirements.

Recently, you talked of plans by the government to deploy a veterinary doctor in every region, and have inspectors in all the 47 counties to help address the menace of quack vets, how far is the initiative?

The plans are still on course. Early this year, the national government recruited 23 veterinary doctors and deployed them to various regions that are under the jurisdiction of the central government. There are ongoing discussions with county governments, through the Council of Governors to employ more vets, so that we can have an inspector in every county to assist weed out the quacks and counterfeit animal drugs and minerals

Climate change is one of the greatest threats to beef production especially for Kenya which relies on pastoralists. Are there measures to mitigate effects of climate in the Asals for continuous meat production?

The main challenges arising from climate change threatening beef production are cycles of droughts, floods due to excess rains, and land degradation as a result of overgrazing and soil erosion by water and wind. However, we have introduced the Kenya Climate Smart Agriculture project to help mitigate effects by ensuring there is adequate availability of forages and fodder pastures and water. We are re-seeding with adaptable pastures such as enteropogon, cenchrus and brachiaria spp. The ministry is targeting to reseed 10,000 acres, so far we have done 2,000 acres.

We have also dug water pans in every Asal, an average of five and four boreholes in each. The ministry is also rolling out of Index-based Livestock Insurance Scheme, which enhances the capacity of climate-vulnerable households to cope and recover from extreme weather effects. The scheme has so far covered 180,000 heads of cattle, but we are targeting 500,000 cattle in 105,000 households.

The country is relying heavily on beef, is the government doing anything to boost consumption of other meats like mutton, pork and poultry products?

The government has come up with various initiatives to address challenges associated with low consumption of mutton, chevon, pork, rabbit and chicken. We are building chicken hatcheries in Marimanti, Tharaka Nithi and Kimose in Baringo County to alleviate supply of day-old chicks. These two facilities will have a capacity of 30,000 chicks per month, increasing supply.

In addition, we are working closely with our researchers based at the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organisation (Karlo), who are breeding improved chicken to increase uptake. We are also planning to build about five chicken slaughterhouses for local farmers to enable them access market. Similar plans for pigs and rabbits are on course. All these initiatives shall be working through national government projects and other stakeholders to support producer groups to increase production and consumption