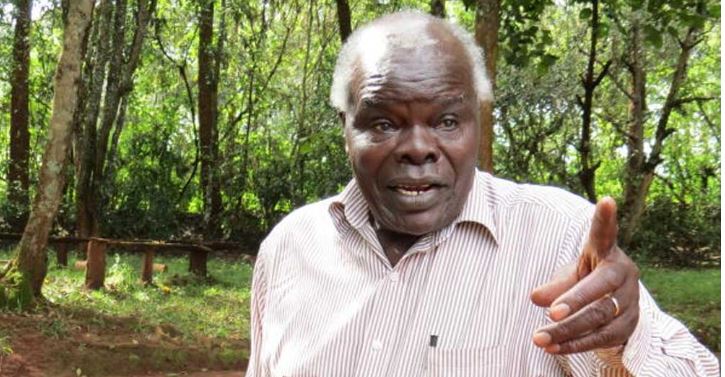

Dr Perez Olindo is a globally acclaimed conservationist who became the first African director of the Kenya National Parks Authority between 1966 and 1981. Olindo became Kenya’s Director of National Parks when he was 27.

Dr Perez Olindo is a globally acclaimed conservationist who became the first African director of the Kenya National Parks Authority between 1966 and 1981. Olindo became Kenya’s Director of National Parks when he was 27.

Now, at the age 81, the Born Free Foundation Kenya patron spoke about poaching, his most memorable encounter with the late President Jomo Kenyatta, Richard Leakey, getting fired over the radio, and running for Lang’ata seat against Raila:

You went to Kakamega High School in the ‘50s. How was it like?

Kakamega boys are lads who love adventure! We did very adventurous things (chuckles). The only thing we did not do was touch a matchbox. That is why the dormitories we found at the school are still there today.

And then you went to America…

I applied as a private student to a university in the US and flew out through the Tom Mboya Airlifts in 1959 to study zoology and wildlife conservation.

What was the culture shock like?

Complete! I didn’t know anything about Americans – what they ate or how they lived. When I got to New York, we were accommodated in a hotel and then dispatched on buses to our various destinations.

From New York to the mid-west was a three-day journey and whenever we had a stop, I would stand in queue behind a lady as they are particular with their choice of food. Whatever they bought, that’s what I also chose!

How did you pay for your studies?

I happened to have the misfortune of lack of funds while at Central Missouri State University, yet we were not allowed to work on a student visa. I approached the dean of students and explained my predicament. He introduced me to a professor who put me in charge of a library of films.

I would deliver or run the equipment in lecture halls and get paid a dollar (Sh100 in current exchange rate) for my services. Later, a US judge who had come to Kenya as a hunter and his friends offered to pay for my fee and also organised for my transfer to Michigan State University.

On your return from the US, what happened?

I came back to Kenya in 1964 during our transition from the colonial rule. I was the only African with a zoology degree and was posted as a biologist in the Game Department at the Coast.

Not long after, the permanent secretary called and instructed me to apply for the position of Deputy Director Supernumerary, National Parks of Kenya, to understudy a British colonel who was the director. In 1966, I took over as director at a very young age. I was barely 27.

How did people react to your appointment as director at such a young age?

There was this colonial military farmer who came to my office. He couldn’t hold himself. “Oh this African government has made a grave mistake.

To take the National Parks of Kenya and give it to a baby?” I was sitting in the director’s seat as he was making that statement!

You were a pilot in the ‘60s…

When I joined National Parks of Kenya, one condition for being confirmed as the deputy director was to learn to fly. The colonial military did not have very high regard for Africans, so they thought this would be a hurdle that would make some of us drop out.

But I got my licence within 90 days of training.

What do you remember about President Jomo Kenyatta?

In 1971 or ‘72, I received a call on my direct line. It was the president. He ordered me to be in his office at State House in 10 minutes flat. I dashed out of my office to my car and broke every traffic rule in the book to beat the deadline.

I found Mzee with about nine freedom fighters from Mt Kenya who wanted permits to collect and sell ivory that they had “hidden” during the Mau Mau rebellion. I was suspicious of the whole scheme and fortunately managed to thwart their plans.

Why was it so difficult to manage elephant and rhino poaching in the 1980s?

Kenya is large and there were people who wanted to lay their hands on rhino horns and ivory because of their international value. We could only effectively protect pockets in the parks. Poaching was mainly taking place outside the parks.

How come you didn’t become the first director of the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS)?

As we came to conclude the creation of KWS in 1989, Richard Leakey succeeded in getting me by-passed by a gang of politicians. Leakey was my sibling as he was the then director of National Museums and he had sworn that he would one day manage the bigger Wildlife Department. That is when I left public service.

You were fired?

I was in the process of establishing Amboseli National Park and was piloting alone from Tsavo to Amboseli when I heard of the appointment of a new director over the one o’clock news.

With that announcement, I flew straight to Nairobi, packed my items and left public service after 14 and a half years.

You are an intellectual and a globally acclaimed conservationist. Why did you want to trade that by running for the Lang’ata parliamentary seat in 1997 and 2002?

I had had it with politicians who lie to the electorate. As soon as they get into office, they don’t even shake the hands of those who voted for them. I was living in Lang’ata then. I was particularly upset by the squalor that the people in Kibera lived in and I was hoping that I could at least provide them with running water.

How did it go?

The old system of thuggery made it physically impossible for me to reach the voters. It was tough. In 2002, there was a female candidate who wanted to become a member of parliament of Lang’ata. There was an ugly scene when she attempted to address a rally at Laini Saba in Kibera.

My opponent’s youth wingers surrounded that woman. They were shouting while she was being raped in broad daylight. That primitive thuggery disgusts me to this day.

What are your views on women?

My wife and I agreed about 12 years ago to transfer our land in one block to our four children with equal ownership.

We didn’t want this family to witness the infighting of sibling rivalry after their parents pass on. Our children, whether boys or girls, have equal rights in our eyes.

Now that you are retired and farming in Kitale, do you miss Nairobi?

Are you out of your mind?! (Pointing at the trees, maize crop and livestock on his expansive farm) Why would I miss Nairobi when I have this?